TLS nonce-nse [zz]

Orig. from Cloudflare

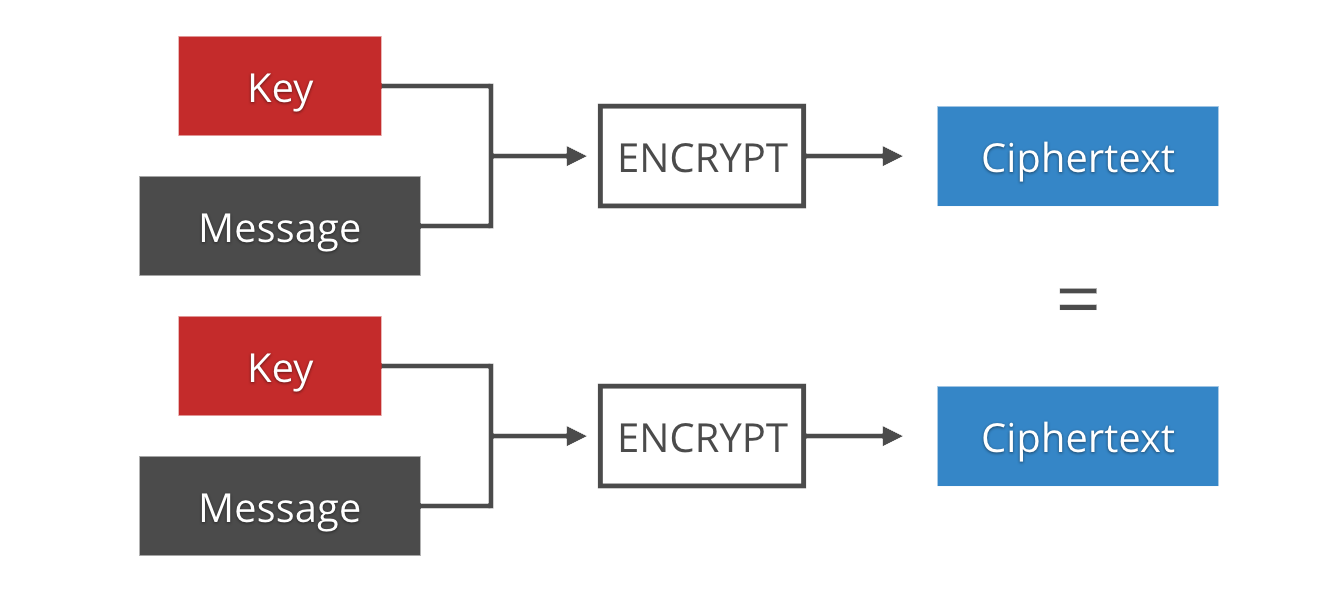

One of the base principles of cryptography is that you can’t just encrypt multiple messages with the same key. At the very least, what will happen is that two messages that have identical plaintext will also have identical ciphertext, which is a dangerous leak. (This is similar to why you can’t encrypt blocks with ECB.)

If you think about it, a pure encryption function is just like any other pure computer function: deterministic. Given the same set of inputs (key and message) it will always return the same output (the encrypted message). And we don’t want an attacker to be able to tell that two encrypted messages came from the same plaintext.

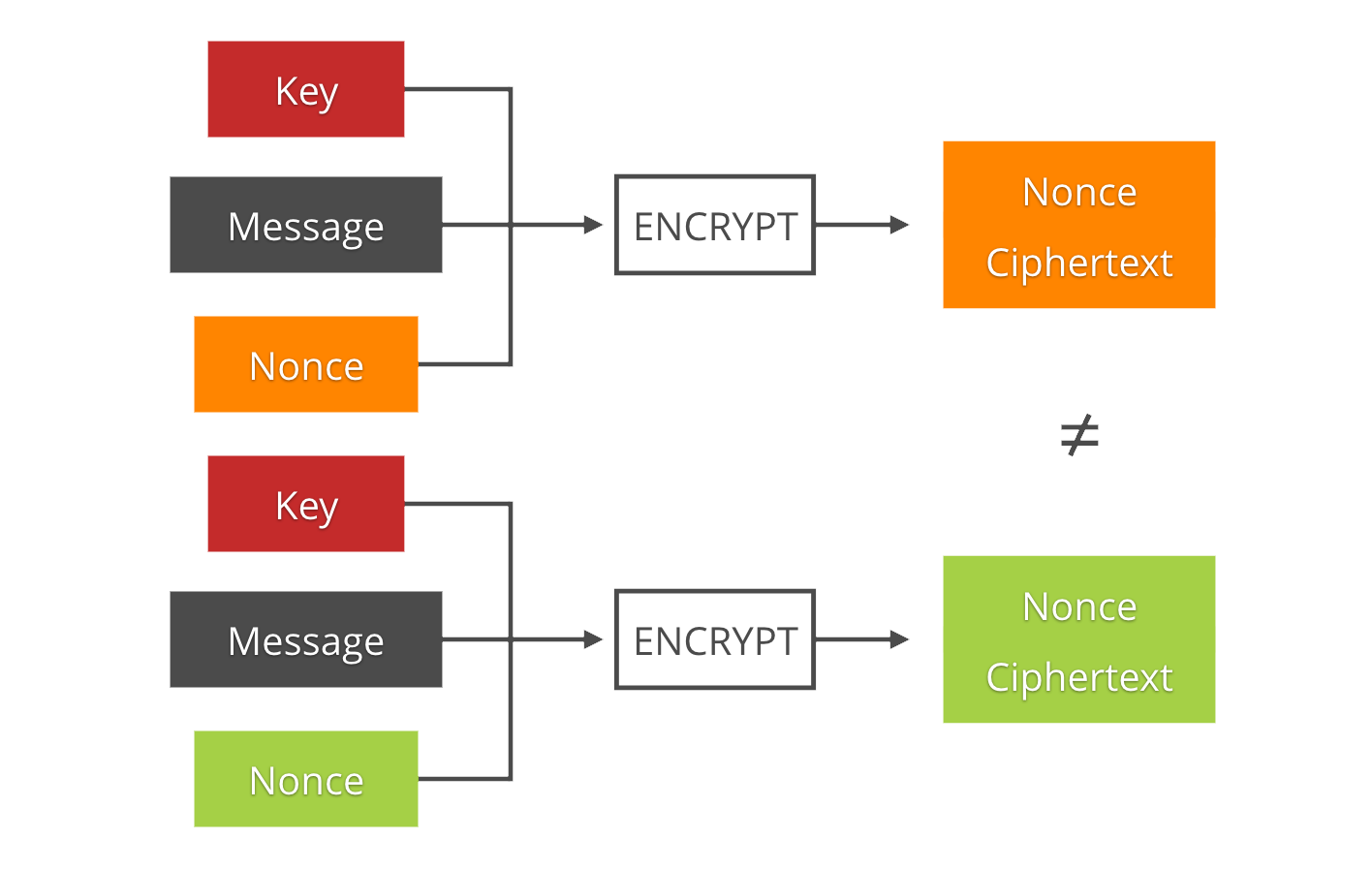

The solution is the use of IVs (Initialization Vectors) or nonces (numbers used once). These are byte strings that are different for each encrypted message. They are the source of non-determinism that is needed to make duplicates indistinguishable. They are usually not secret, and distributed prepended to the ciphertext since they are necessary for decryption.

The distinction between IVs and nonces is controversial and not binary. Different encryption schemes require different properties to be secure: some just need them to never repeat, in which case we commonly refer to them as nonces; some also need them to be random, or even unpredictable, in which case we commonly call them IVs.

Nonces in TLS

TLS at its core is about encrypting a stream of packets, or more properly “records”. The initial handshake takes care of authenticating the connection and generating the keys, but then it’s up to the record layer to encrypt many records with that same key. Enter nonces.

Nonce management can be a hard problem, but TLS is near to the best case: keys are never reused across connections, and the records have sequence numbers that both sides keep track of. However, it took the protocol a few revisions to fully take advantage of this.

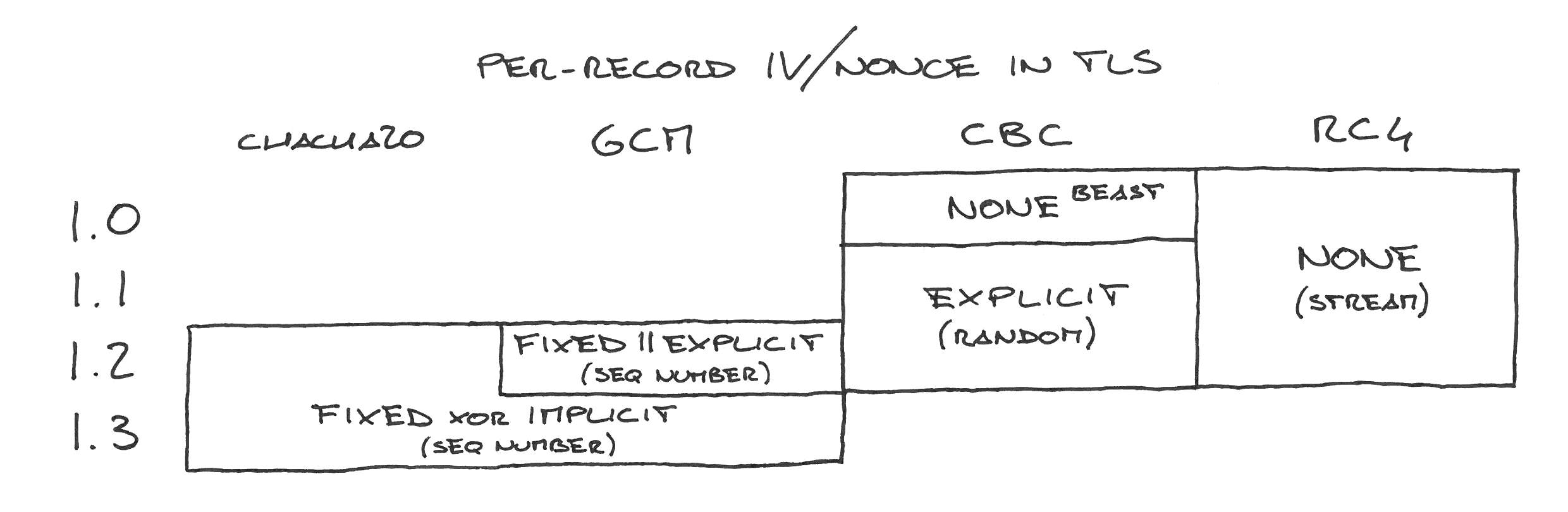

The resulting landscape is a bit confusing (including one or two attack names):

RC4 and stream ciphers

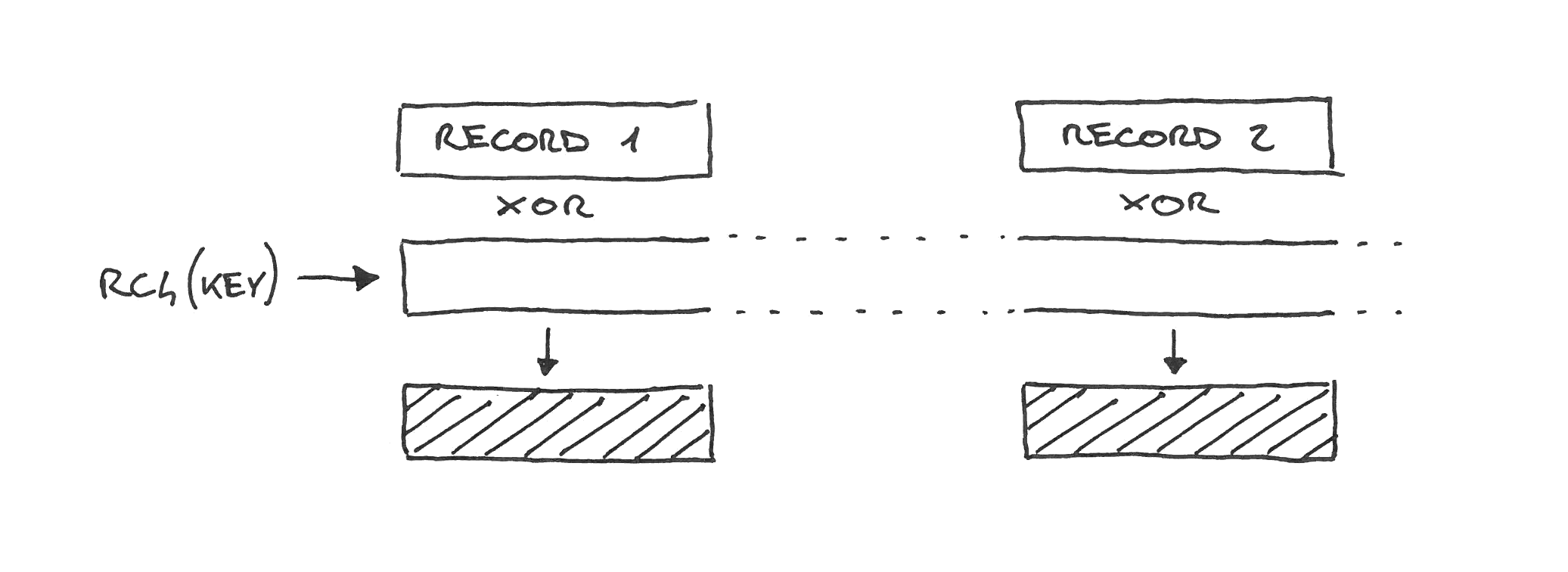

RC4 is a stream cipher, so it doesn’t have to treat records separately. The cipher generates a continuous keystream which is XOR’d with the plaintexts as if they were just portions of one big message. Hence, there are no nonces.

RC4 is broken and was removed from TLS 1.3.

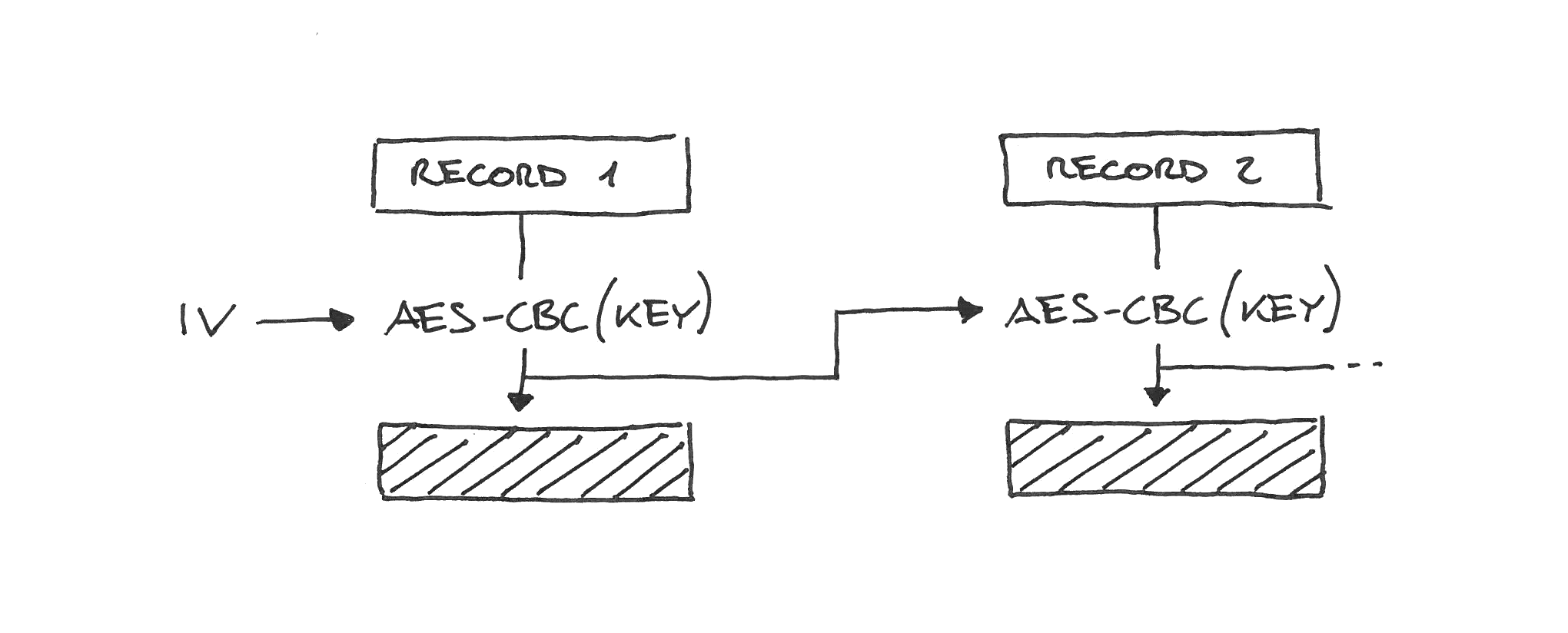

CBC in TLS 1.0

CBC in TLS 1.0 works similarly to RC4: the cipher is instantiated once, and then the records are encrypted as part of one continuous message.

Sadly that means that the IV for the next record is the last block of ciphertext of the previous record, which the attacker can observe. Being able to predict the IV breaks CBC security, and that led to the BEAST attack. BEAST is mitigated by splitting records in two, which effectively randomizes the IV, but this is a client-side fix, out of the server control.

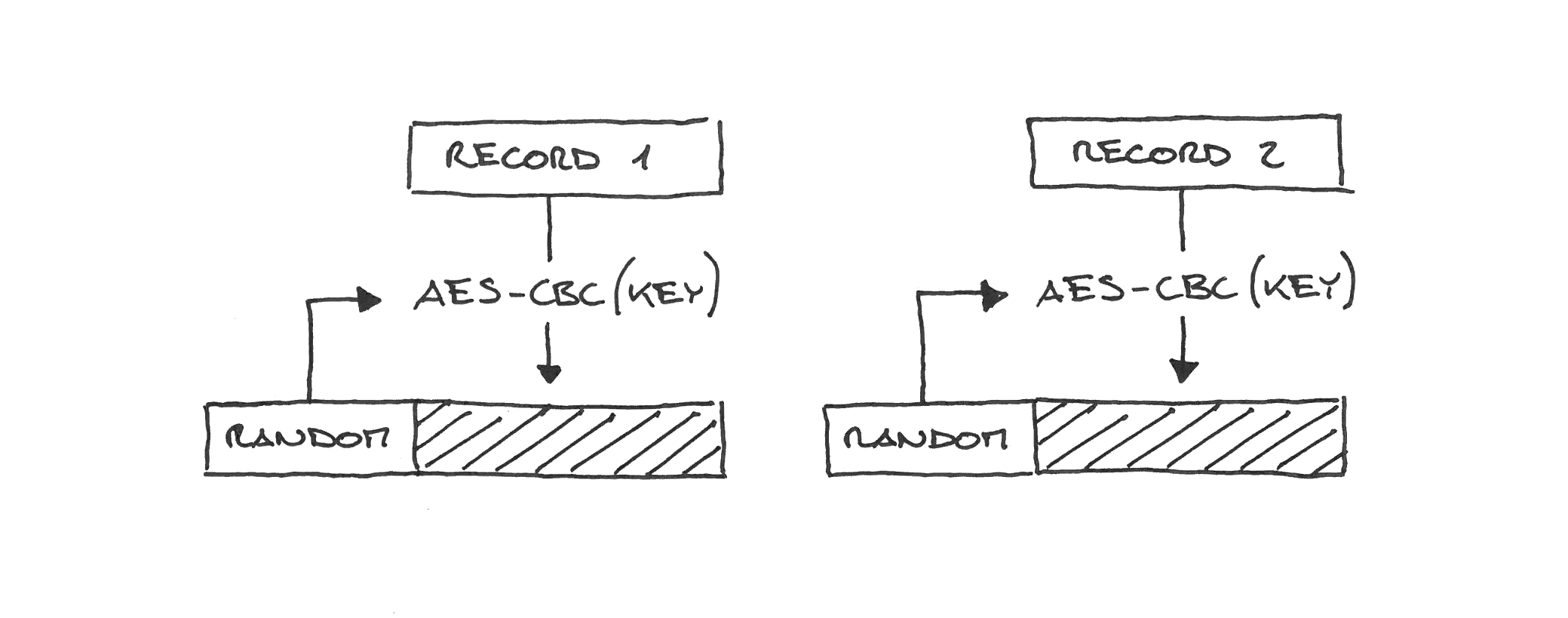

CBC in TLS 1.1+

TLS 1.1 fixed BEAST by simply making IVs explicit, sending the IV with each record (with the network overhead that comes with that).

AES-CBC IVs are 16 bytes (128 bits), so using random bytes is sufficient to prevent collisions.

CBC has other nasty design issues and has been removed in TLS 1.3.

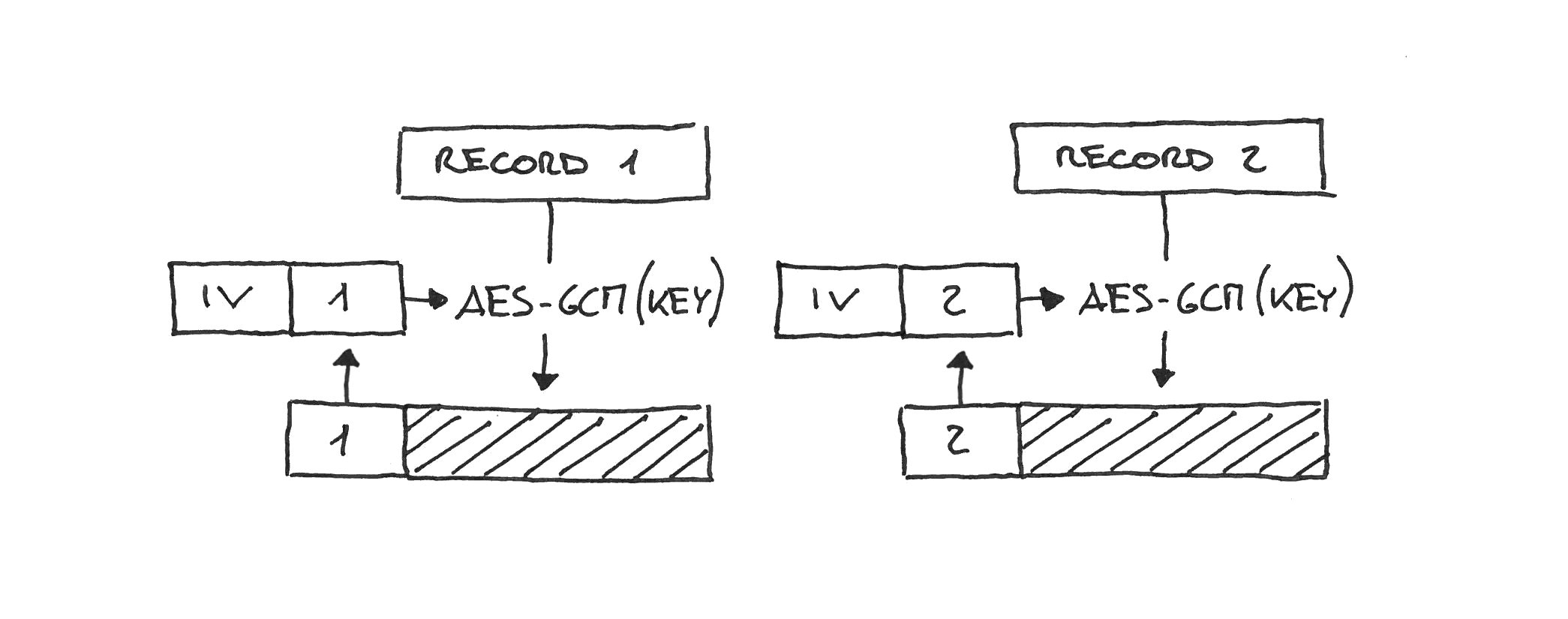

TLS 1.2 GCM

TLS 1.2 inherited the 1.1 explicit IVs. It also introduced AEADs like AES-GCM. The record nonce in 1.2 AES-GCM is a concatenation of a fixed per-connection IV (4 bytes, derived at the same time as the key) and an explicit per-record nonce (8 bytes, sent on the wire).

Since 8 random bytes is too short to guarantee uniqueness, 1.2 GCM implementations have to use the sequence number or a counter. If you are thinking “but what sense does it make to use an explicit IV, sent on the wire, which is just the sequence number that both parties know anyway”, well… yeah.

Implementations not using a counter/sequence-based AES-GCM nonce were found to be indeed vulnerable by the “Nonce-Disrespecting Adversaries” paper.

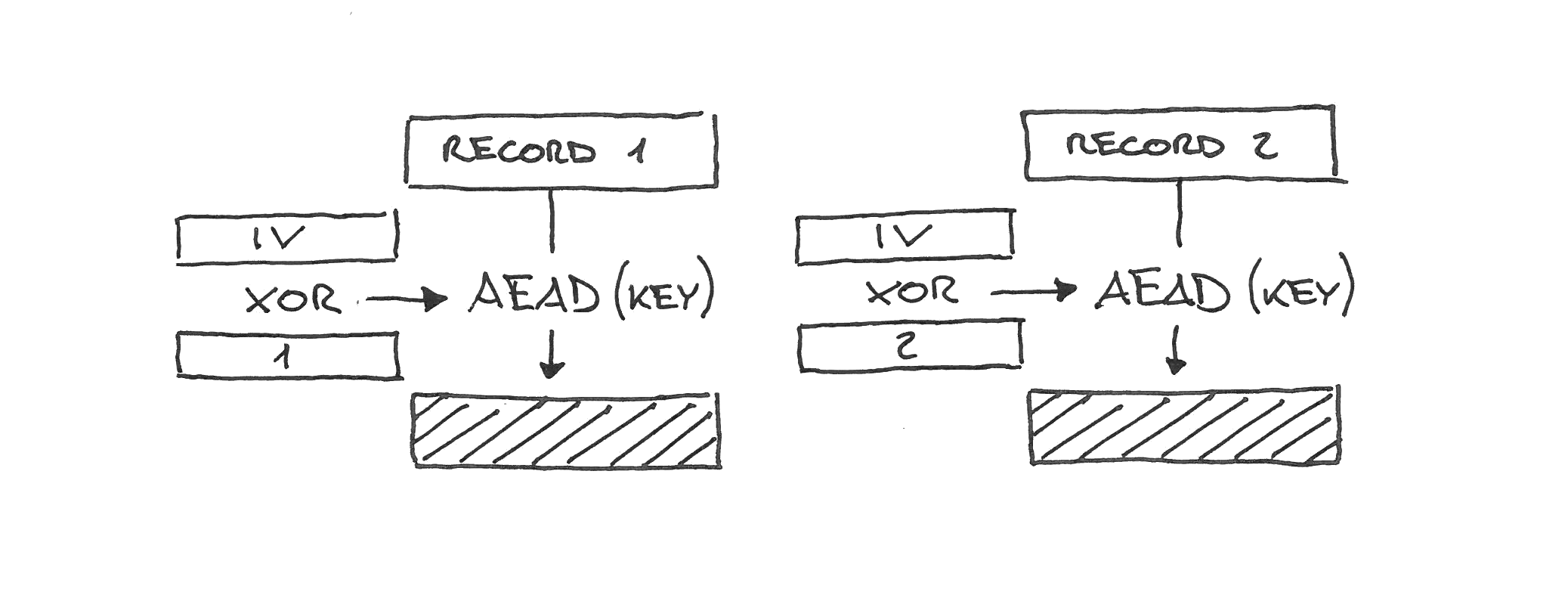

TLS 1.3

TLS 1.3 finally took advantage of the sequential nature of TLS records and removed the free-form explicit IVs. It uses instead a combination of a fixed per-connection IV (derived at the same time as the key) and the sequence number, XORed—not concatenated.

This way the entire nonce length is random-looking, nonces can never be reused as the sequence number monotonically increases, and there is no network overhead.

ChaCha20-Poly1305

The ChaCha20-Poly1305 ciphersuite uses the same “fixed IV XORed with the sequence number” scheme of TLS 1.3 even when used in TLS 1.2

While 1.3 AEADs and 1.2 ChaCha20 use the same nonce scheme, when used in 1.2 ChaCha20 still puts the sequence number, type, version and length in the additional authenticated data. 1.3 makes all those either implicit or part of the encrypted payload.

To recap

- RC4 is a stream cipher, so it has no per-record nonce.

- CBC in TLS 1.0 used to work similarly to RC4. Sadly, that was vulnerable to BEAST.

- TLS 1.1 fixed BEAST by simply making IVs explicit and random.

- TLS 1.2 AES-GCM uses a concatenation of a fixed IV and an explicit sequential nonce.

- TLS 1.3 finally uses a simple fixed IV XORed with the sequence number.

- ChaCha20-Poly1305 uses the same scheme of TLS 1.3 even when used in TLS 1.2.

Nonce misuse resistance

In the introduction we used the case of a pair of identical message and key to illustrate the most intuitive issue of missing or reused nonces. However, depending on the cipher, other things can go wrong when the same nonce is reused, or is predictable.

A repeated nonce often breaks entirely the security properties of the connection. For example, AES-GCM leaks the authentication key altogether, allowing an attacker to fake packets and inject data.

As part of the trend of making cryptography primitives less dangerous to use for implementers, the research is focusing on mitigating the adverse consequences of nonce reuse. The property of these new schemes is called Nonce Reuse Resistance.

However, they still have to see wider adoption and standardization, which is why a solid protocol design like the one in TLS 1.3 is critical to prevent this class of attacks.